It had potential but desperately needed refurbishing and a paint job. To bring in more light, two walls were torn down and replaced with glass. The back of the building was lopped off to build a road to the nearest metro station and a second-floor exhibition space was added. This kind of renovation could take years in most other cities, not to mention the time needed to organize a major art fair. “It only took us eight months,” Mr. Zhou said matter of factly, just in time for the inaugural West Bund Art & Design fair in September 2014.

Around the same time, local leaders persuaded the Chinese-Indonesian tycoonBudi Tek to move in. A former poultry magnate, Mr. Tek had spent a considerable chunk of his fortune collecting Chinese art over the last decade and was looking to build his own museum in China, preferably in Shanghai, his wife’s hometown. “When I first committed to this place, there was no West Bund,” Mr. Tek said. It was still, he added, “a vision.” Soon after, he found a former airplane hangar and hired the Japanese architect Sou Fujimoto to renovate it.

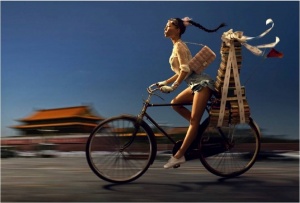

Mr. Tek’sYuz Museum opened in May 2014 with a statement piece in its striking, glass-covered atrium: a live olive tree planted in a giant block of dried earth, a work by the Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan. Inside were more innovative installations, many owned by Mr. Tek, that could fit only inside a hangar, such as Xu Bing’s “Tobacco Project,” an assemblage of more than 600,000 cigarettes resembling a tiger skin rug; and “Freedom” by Sun Yuan and Peng Yu, a giant metal tank with a high-pressure hose inside that comes to life every hour, spraying the portholes with frightening jolts of water to the squeals of camera-snapping crowds.

Few museums in China open with such a bang — and then maintain the momentum over the long haul. Yuz has managed to do so thus far, in part because Mr. Tek’s art-world connections have helped the museum deliver varied, quality programs.

Showing until Dec. 31 is one of Yuz’s latest acquisitions, Random International’s “Rain Room,” an interactive water installation that drew long lines when it was shown two years ago at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Then, two blockbuster exhibitions will follow: the first China solo show of Alberto Giacometti’s sculptures in collaboration with the Giacometti Foundation (March 2016), and an exhibition in conjunction with the Picasso Museum in Paris (2017).

“I call myself a start-up museum,” Mr. Tek said. “To make a statement to the world that we are a serious museum, we want to do very exciting programs. … Museums are not for ants, birds — they’re for people to come, as many people as you can.”

This philosophy is shared by the Chinese collectors Wang Wei and her husband, Liu Yiqian, a taxi-driver-turned-multimillionaire-financier, who have also made names for themselves with eye-catching art purchases in recent years. Last year, they shattered two international auction records in Hong Kong: In April, Mr. Liu paid $36 million for a Ming dynasty porcelain cup, nicknamed the chicken cup, which at the time was the most ever spent on Chinese porcelain at auction. Months later, he paid $45 million for a 600-year-old embroidered silk tapestry, a record at the time for any Chinese artwork sold at auction.

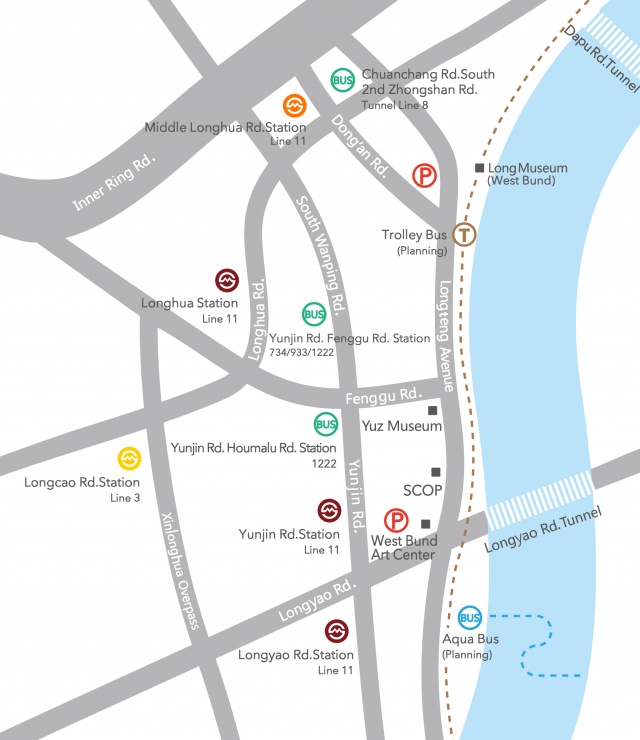

After building a sizable collection, Mr. Liu and his wife began looking for space to build museums in Shanghai to exhibit their purchases. Again, the Xuhui district government came through with a plum spot on the West Bund riverfront, a wharf where coal was unloaded from barges throughout much of the 20th century. A 1950s-era concrete bridge that was used to transport coal to train hoppers was preserved, and the Shanghai architecture firm Atelier Deshaus constructed a new museum around it with a similarly stark, concrete design.

The Long Museum West Bund also opened in early 2014, displaying many pieces from the couple’s nearly 1,900-piece personal collection. Earlier this year, the “chicken cup” was exhibited for a brief time in a darkened room, lit dramatically from above, with two guards posted at the doors.